Can we talk about such a phenomenon as Russian Impressionism? The Depicting the Air exhibition dispels all doubts.

The exhibition Depicting the Air. Russian Impressionism is an opportunity to take preliminary stock of the work of the Museum of Russian Impressionism, which opened in 2016. What has been done in nine years — exhibitions, books, inclusive projects — has convinced even desperate skeptics that Russian Impressionism really existed. And now it’s time to talk more seriously about its phenomenon.

One of the points of reference for Russian Impressionism was the work of Vasily Polenov. During a trip to Europe in the 1870s, he was inspired by the findings of French artists, although he never became a pure Impressionist. And yet, painting en plein air, the attempt to capture a fleeting impression, and the focus on the light and atmospheric environment were all reflected in his works. He was the first to dare to show his sketches — at the 13th exhibition of the “Peredvizhniki” (Wanderers) movement in 1885. Interest in this seemingly “secondary” genre was also shown by Isaac Levitan — not an Impressionist either but a subtle master of the Russian landscape, capable of capturing the finest nuances of nature’s moods.

However, the true “full-blooded” Impressionist was, of course, Konstantin Korovin. Perhaps he is the only one of the major Russian artists who forever remained faithful to this direction. Moreover, he didn’t borrow Impressionism from the French; he arrived at it on his own. A special role in his work was played by “nocturnes” — depictions of illuminated summerhouse verandas with deep blue twilight outside the window, as well as nighttime Paris, glowing with lights. These things turned out to have many imitators, which allowed the creators of the exhibition to make a separate section “Black Impressionism.” In addition to Korovin, here you can see the virtually indistinguishable Vasily Meshkov with his Boulevard in Paris.

However, for most Russian artists, Impressionism was not a lifelong pursuit; they dedicated only one or two paintings or a specific period of their work to it. For example, the star of the Russian avant-garde, Mikhail Larionov, started out as an Impressionist. The exhibition features two large paintings — Oxen Resting and Camels — which are quite unlike his later experiments in the style of Rayonism. Or Igor Grabar: the delicate Winter and bright Apples are examples of his early work, marked by the influence of Impressionism. Even Nikolay Kasatkin, a former Peredvizhnik who painted workers and political figures, has works like Nude Model, featuring flashes of red, green, and brown hues. Overall, the exhibition’s creators lead viewers to the idea that Russian Impressionism was not a phenomenon with clear temporal boundaries or associated with a specific group of artists. Many of our artists experienced the influence of the French method — to a greater or lesser extent.

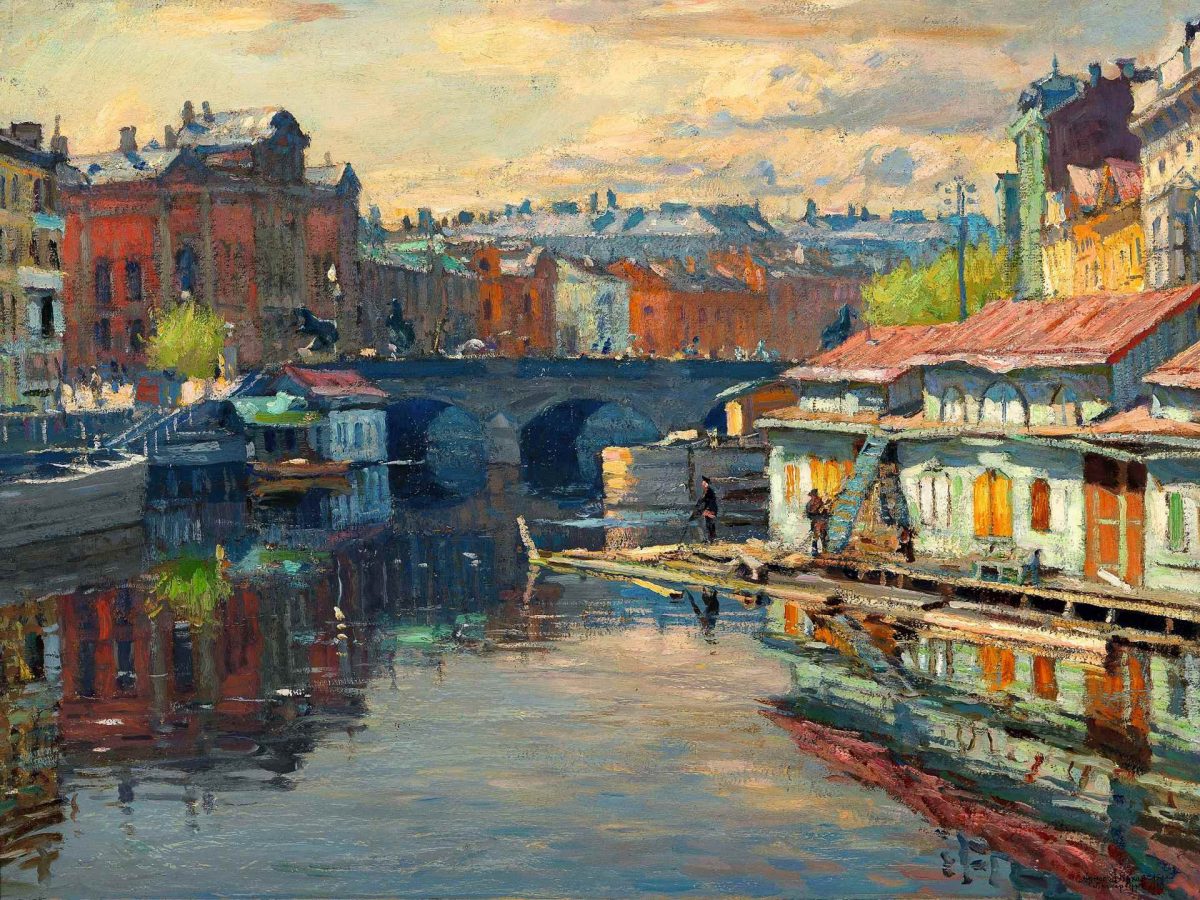

What then are the peculiarities of Russian Impressionism? For example, the interest in still life was driven by something as simple as the climate: painting en plein air in winter is inconvenient, and the daylight hours are short, so all the work shifts to the artist’s studio. Another characteristic is urban landscapes, which differ strikingly from how the French depicted Paris. Our artists were not drawn to the noise and glamour of big cities but rather to their cozy, old-fashioned corners. For example, in Arnold Lakhovsky’s painting, we see a bustling market day, while Leonid Turzhansky depicts Moscow built up with low-rise mansions.

A common feature of Russian and French Impressionism was their attention to Japanese art. Our artists were inspired by unusual techniques, particularly fragmentary composition. Here, Konstantin Kuznetsov’s gaze whimsically captures three trees in the foreground — only their trunks, without the canopy — a technique used, for example, by Hokusai.

By 1910, Impressionism in Russia had already become a familiar phenomenon, almost a classic, and new figures emerged on the artistic stage. Those who remained true to the Impressionist style began to paint more vibrantly — Nikolay Tarkhov, in particular. Overall, the Impressionists managed to spark a revolution — “casting off the prim academicians from the ship of modernity” and steering art in a completely different direction: “realism” gave way to experiments with form. This was also influenced by scientific discoveries of the time — such as those in the field of light physics, which is echoed by the most unexpected exhibit in the exhibition: the installation Visual Aids by contemporary artist Irina Korina. The colorful, shimmering objects reference scientific theories and diagrams, while one of them, in its shape, resembles a gazebo — a tribute to a theme favored by Russian Impressionists. And considering that a work by Irina’s great-great-grandfather, the artist Alexei Korin, accidentally ended up in the exhibition, there is no doubt — the line between past and present is even easier to draw than it seems.

Until June 1.

Photo: press-office