According to the Lunar Calendar, the symbol of the year 2024 is the Green Wooden Dragon, the most important character in Chinese culture and a central figure in East Asian folklore. Asian nations depict dragons with particular awe and respect. That said, European culture has also developed its own unique relationship with dragons.

China: The Dragon’s Realm

The Chinese Dragon Lun is one of the four great mystical creatures, alongside the Unicorn, the Phoenix, and the Turtle. Legend has it that Lun has nine dragon sons, each possessing a unique personality. The individual characteristics of dragons dictate where their images are placed in the architecture of a traditional Chinese house. For instance, Chiwen will eat just about anything, so his likeness is positioned on rooftops to consume ill winds, preventing them from reaching humankind. Pulao, who loves to shout, is considered the protector of music and gets depicted on gongs and bells. Jiaotu, meanwhile, despises being disturbed by strangers, hence his place is on the door handle.

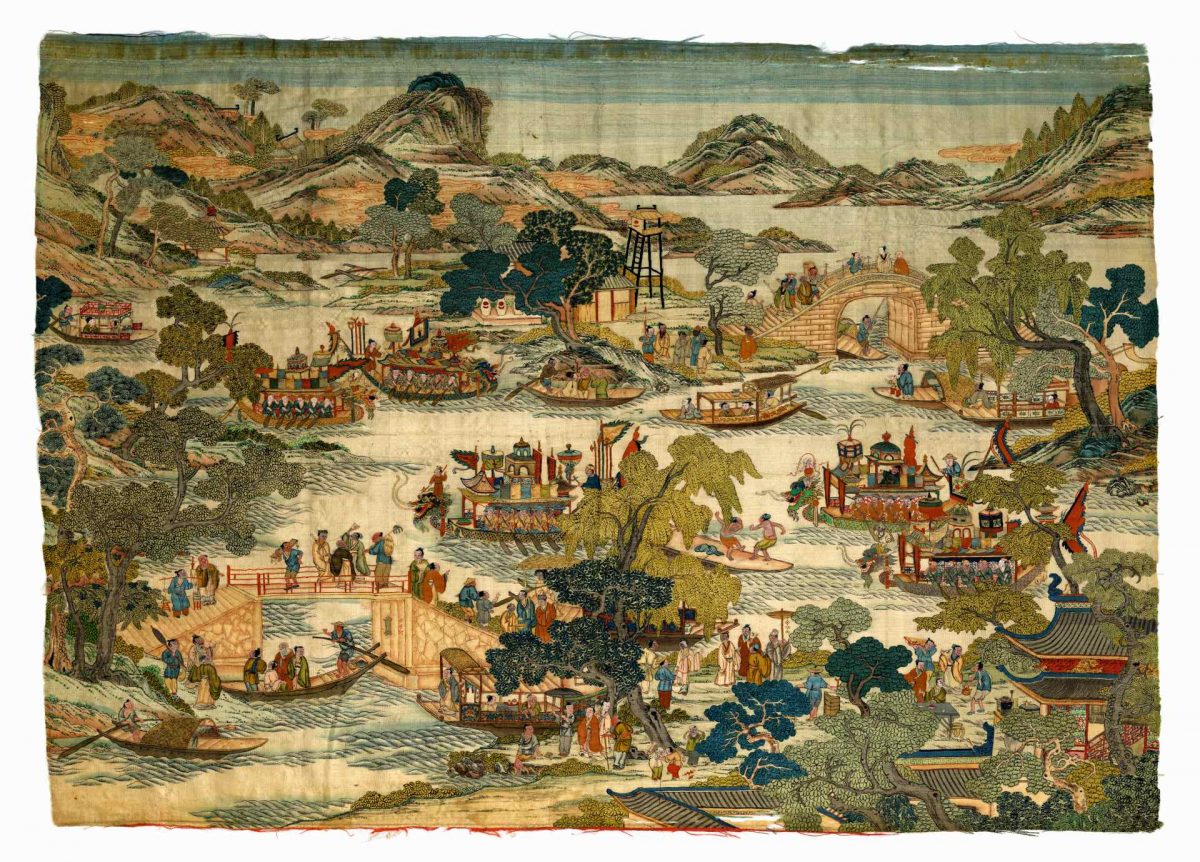

In China’s contemporary culture, the Dragon Boat Festival is experiencing a revival. The festival gets its name from the day’s main event: a rowing competition in boats designed to resemble dragons. Legends say that on this very date, a river dragon killed the folk hero and China’s first poet Qu Yuan in a fit of blood lust rather uncommon for Asian wyrms. This bone-chilling legend obscured factual historical events in the people’s memory, and with time, the somber search for a drowned body transformed into joyful competition on brightly adorned boats. The Chinese dragons’ closest kin are the Japanese dragons. That said, they also borrow some of their traits from the Indian serpent people, the Nagas, and have much more claws. In Japan, just like in China, the dragon often favors humans, although it can sometimes be whimsical and spiteful. And similarly, Japan has its own tradition of using dragon imagery in room decor, embroidery, and ornaments.

Dragons and Saints

The influx of Chinese luxury items into Western culture, which sparked the chinoiserie trend, surprisingly did not really alter the Europeans’ perception of dragons. In European iconography, the dragon has historically been a symbol of evil that the hero must battle and the heroine must miraculously escape, lest she be devoured. St. George is the first figure that comes to mind here, having saved a king’s only daughter from this ferocious beast. A mounted knight wielding a spear, a fearsome dragon with its gaping maw, a beautiful maiden, a rock-side cave: these elements are always easy to recognize in artistic renditions of the tale. In some stories, however, the dragon does not get slain. For instance, St. Sylvester tamed a wyrm through prayer, inspiring Roman priests to convert to Christianity. St. Margaret, who was swallowed by a dragon, managed to escape from the monster’s belly unharmed, guided by her faith. Even St. Martha of Bethany, famous for hosting Christ in her home, once had an encounter with a dragon. The Golden Legend, written in the mid-13th century by chronicler Jacobus de Voragine, mentions that after wandering for a long time, Martha and her siblings Lazarus and Mary found themselves in what is now Tarascon, France. Impressed by Martha’s holy presence, eloquence, and indomitable spirit, the locals asked her to drive away the terrifying dragon that had taken up residence in the nearby river. Martha came upon the creature as it was in the middle of devouring some unfortunate soul, blessed it with a sign of the cross, and doused it with holy water. This turned the dragon as docile as a lamb, allowing the Saint to restrain it with her own belt. However, the dragon’s fate was tragic — it was slain by the very people it had tormented.

Dungeons Full of Dragons

As interest in mythological heritage surged in the 19th century, artists started utilizing dragon imagery more and more often. Such depictions can be found in the works of Victorian fairy tale painters, but the true renaissance of dragon art began in the last third of the 20th century and continues to this day.

The evolution of the fantasy genre sparked a dragon boom in both analog illustration and digital art. It’s difficult to determine what boosted the creatures’ popularity more — the cult following around Tolkien, the writer behind the famous Smaug, or the advent of the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, which has inspired countless books, films, and animated series. Regardless, dragons have become a staple in our lives, appearing in droves everywhere from book covers and smartphone wallpapers to badges and T-shirts, irrespective of the Lunar Calendar.