The exhibition Square and Space. From Malevich to GES-2 became the hit of the season in Moscow. Let’s talk about what you can’t miss.

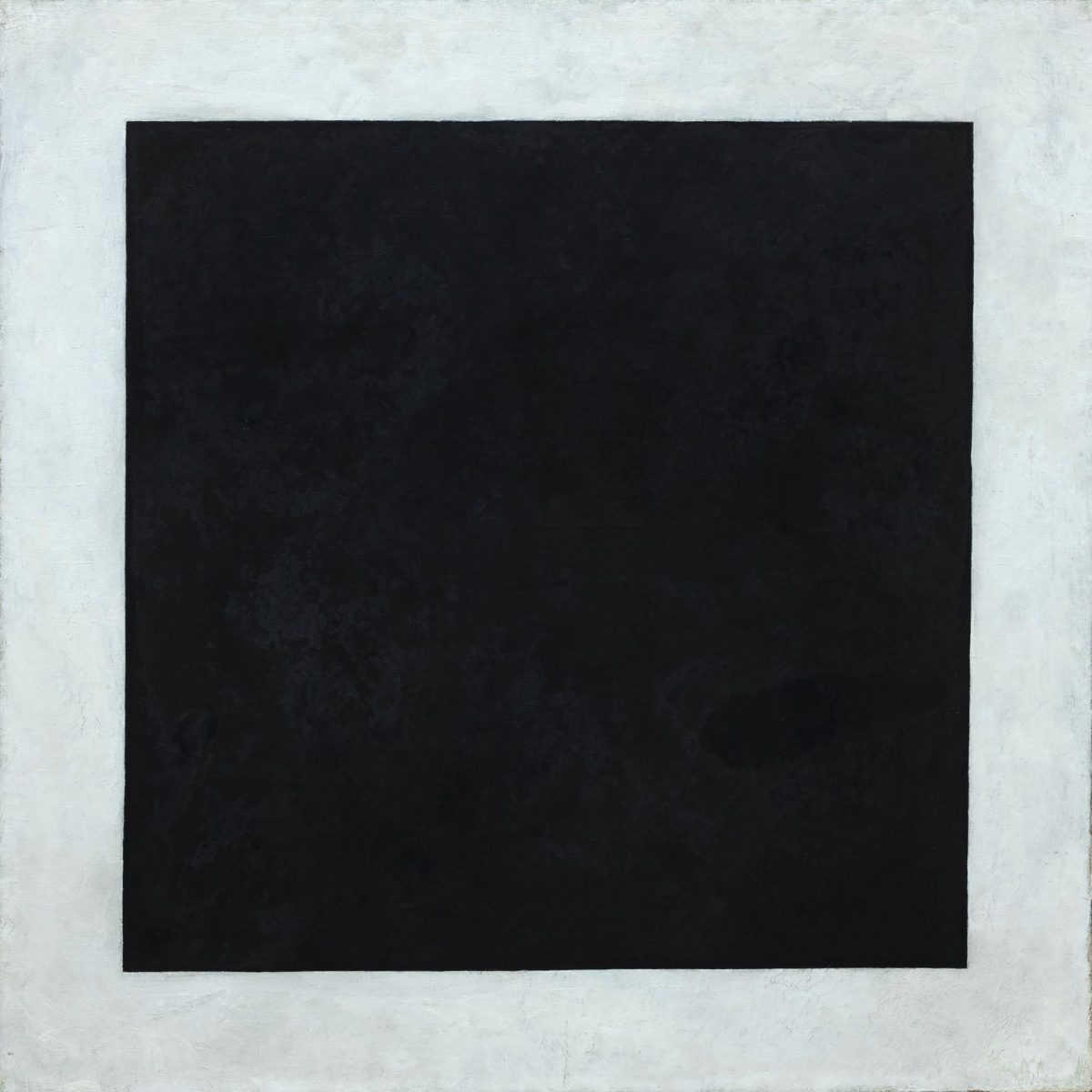

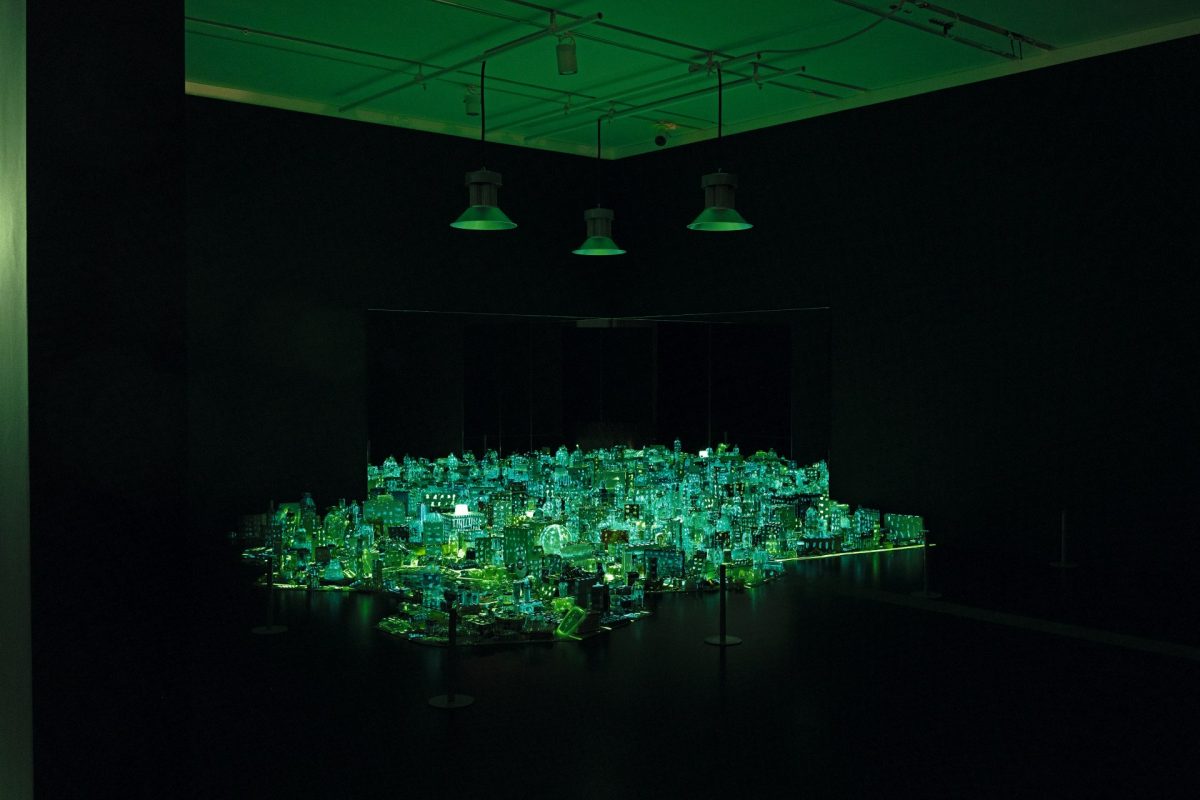

You rarely see works by Bulatov, Rodchenko, Shelkovsky, Gormley, Kiefer, Picasso, Basquiat, and Warhol in the same venue. However, this exhibition not only has a brilliant international cast but also an unusual concept. One of its “participants” was the building of GES-2 itself — a former power plant, transformed by the star Italian architect Renzo Piano into a light openwork House of Culture: modern, though, without Soviet connotations. Black Square by Kazimir Malevich became a coherent point of reference in this exhibition. The artist’s refusal to imitate reality once had a bombshell effect. Art gained self-value and became a “thing in itself.” However, it then spilled out onto the streets of cities — for example, in the experiments of the constructivists — and changed the reality we are accustomed to. At the same time, reality also influenced art: for example, the advent of reinforced concrete structures gave rise to new architectural forms. That is why the idea of presenting the exhibition space in the form of a city — with streets and intersections — looks quite natural. The musical connotations — the exhibition consists of 12 sections with a prologue and an interlude — seem not accidental: architecture, as we know, is frozen music. See the most interesting things in our review.

“From image to pure color”

Malevich’s insights not only separated art from reality but also made form and color independent of each other. The latter has played a subordinate role in paintings for centuries but has now thrown off its shackles. Strictness of black and white (Kazimir Malevich. Four Squares), which put an end to previous ideas about art, prompted Alexander Rodchenko to write his own version of “absolute zero” — Black on Black, No. 81. From this “nothingness,” color eventually broke free — in Rodchenko’s triptych Pure Red, Pure Yellow, Pure Blue. It is noteworthy that the artist considered this work to be the end of easel painting: after it, he took up production art. However, the baton was eventually picked up by representatives of geometric abstraction in postwar art.

“Symbol and gesture”

What is more in the creations of 20th-century artists — calculation or spontaneity? Improvisation by Vasily Kandinsky seems to have been created in a burst of inspiration, but a lot of work preceded it. The artist thought a lot about the relationship between color and sound — and could literally hear color and see music. In turn, the painting Naval Battles Recur Every 317 Years by German artist Anselm Kiefer is inspired by the thoughts of Russian futurist, brilliant and eccentric Velimir Khlebnikov, who believed in the cyclical nature of naval battles: numbers and mysticism are surprisingly combined here. Well, the joint creation of Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat (Untitled) surely required the authors to find compromises and restrain their creative impulses.

“Man”

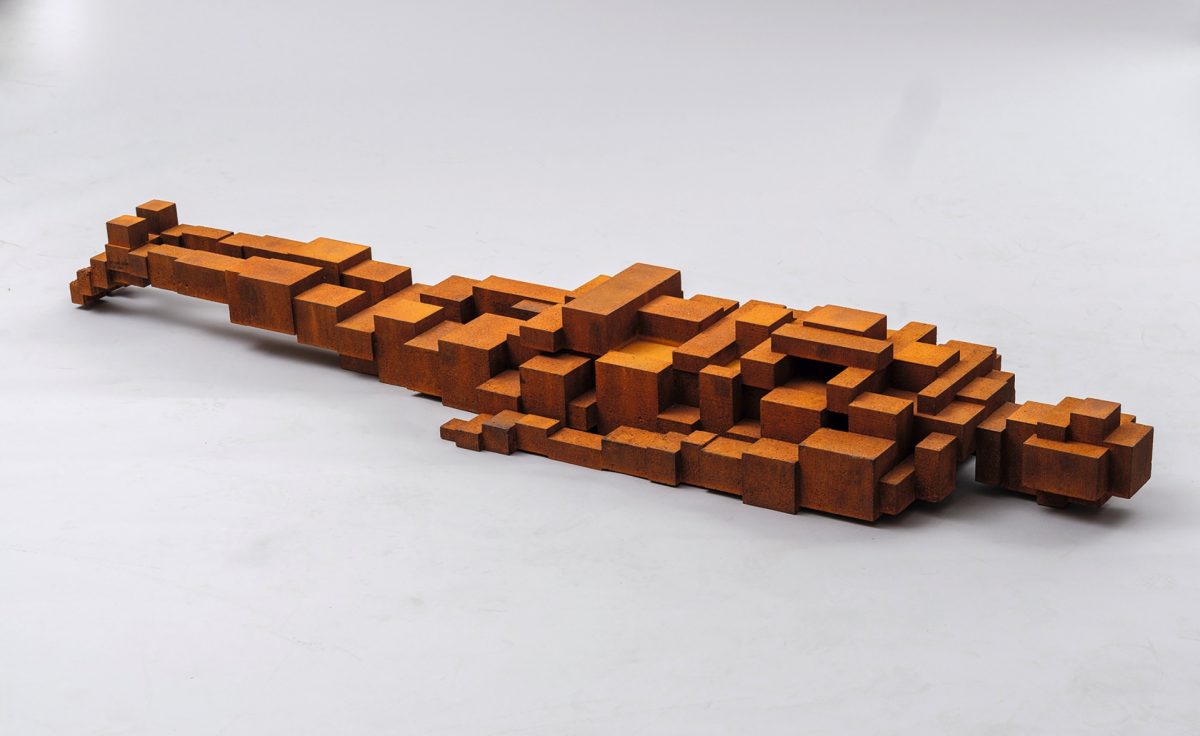

The 20th century was marked by the crisis of anthropocentrism: man suddenly ceased to be the measure of all things, and this could not but affect art. All the more so when questions arose as to how to depict a person, because the criterion of resemblance had lost its relevance. British sculptor Antony Gormley is one of those who still addresses the human body but does so in his own way. His cast-iron anthropomorphic figure (Level), modeled by the sculptor himself, seems to be made of pixels. Russian viewers could see the object in the antique halls of the Hermitage, where the Gormley exhibition was held in 2011. A rethinking of the familiar space, as well as the attitude to art itself, is what the British master achieves.

“Playing with a square”

Black Square reformatted the consciousness not only of Western artists but also of their Soviet colleagues — those who belonged to unofficial art. The influence of the avant-garde can also be traced in the work of Igor Shelkovsky, one of the main representatives of Soviet nonconformism. In Cloud, he combines painting and sculpture, transforming the soft and light into the weighty, rough, and visible. Instead of rounded forms, the viewer sees wooden blocks of different sizes covered with blue and white enamel. Can the elusive and the objectless be shackled in rectangles? The experiment, as we see, turns out to be quite successful.

The exhibition will be open until October 27.

Photo: press office