On January 9, the famous film director and artist Sergei Parajanov would have turned 100 years old. And while his actual journey turned out to be much shorter — he lived to be only 66 — it was full of bright, extraordinary adventures. Here are just a few highlights.

A love of old things

Parajanov probably inherited this quality from his father, who traded in antiques. The director himself treated the most trivial trinkets with utmost reverence, being able to find value even in something glaringly dilapidated. His residence was filled with antique furniture, ancient icons, and beautiful fabrics. As a true aesthete, he preferred his bread and cheese finely sliced, and dressed his guests into fantastical outfits, as if crafting his own magical world out of the unsightly reality. But at the same time, he easily parted with material possessions. He could bestow a king’s ransom upon a complete stranger, and sometimes would gift back presents intended for him. Turning it all into a stunning mini-performance in the process.

Recognition at 40

Parajanov’s first films did not impress his contemporaries. They were quite mainstream, in the spirit of socialist realism, and nothing about them hinted that a star was about to be born. But everything changed after Parajanov watched Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Ivan’s Childhood (1962). Two years later, he shot Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, a strange and poetic story of Hutsul Romeo and Juliet that differed starkly from his previous works. Through this motion picture, which won awards at the Rome and Thessaloniki film festivals, Parajanov became one of the leaders of the Soviet New Wave.

A true Renaissance man

Parajanov could sing in a beautiful dramatic tenor and had memorized all the operas that were performed at the Tbilisi Opera Theater. In fact, his initial plan for making it big in Moscow was to become a singer. He even studied at the Moscow Conservatory for some time before switching to film making. He also had another passion, and retained it until the very end of his life: fine art. He made amazing collages out of pottery shards, peacock feathers, old Christmas ornaments, dolls, and even clothespins. His films, especially The Color of Pomegranates (1968), resemble colorful patchwork. Even when his free spirit and sharp tongue landed him behind bars, he tried to mold his new frightening, alien surroundings to match his imagination, and taught his prisoners to create collages.

Friendship with Lilya Brik

Parajanov and Mayakovsky’s muse became acquainted in 1973. He came to their first meeting not with a traditional bouquet, but with a single huge violet in a flowerpot. As the eccentric Lilya appreciated people that stood out from the crowd, they instantly got along. She cherished the collages Parajanov sent her from prison, and eventually helped him regain his freedom. Despite her advanced age, she traveled to Paris — under the formal pretext of attending the “20 Years of Mayakovsky’s Work” exhibition — where she met the poet Louis Aragon, husband of her sister Elsa Triolet. Brik persuaded Aragon to fly to Moscow and accept the Order of Friendship of Peoples awarded to him by the Soviet government. During his meeting with Brezhnev, the poet put in a good word for the imprisoned film maker, and he was released early.

Parajanov’s thaler

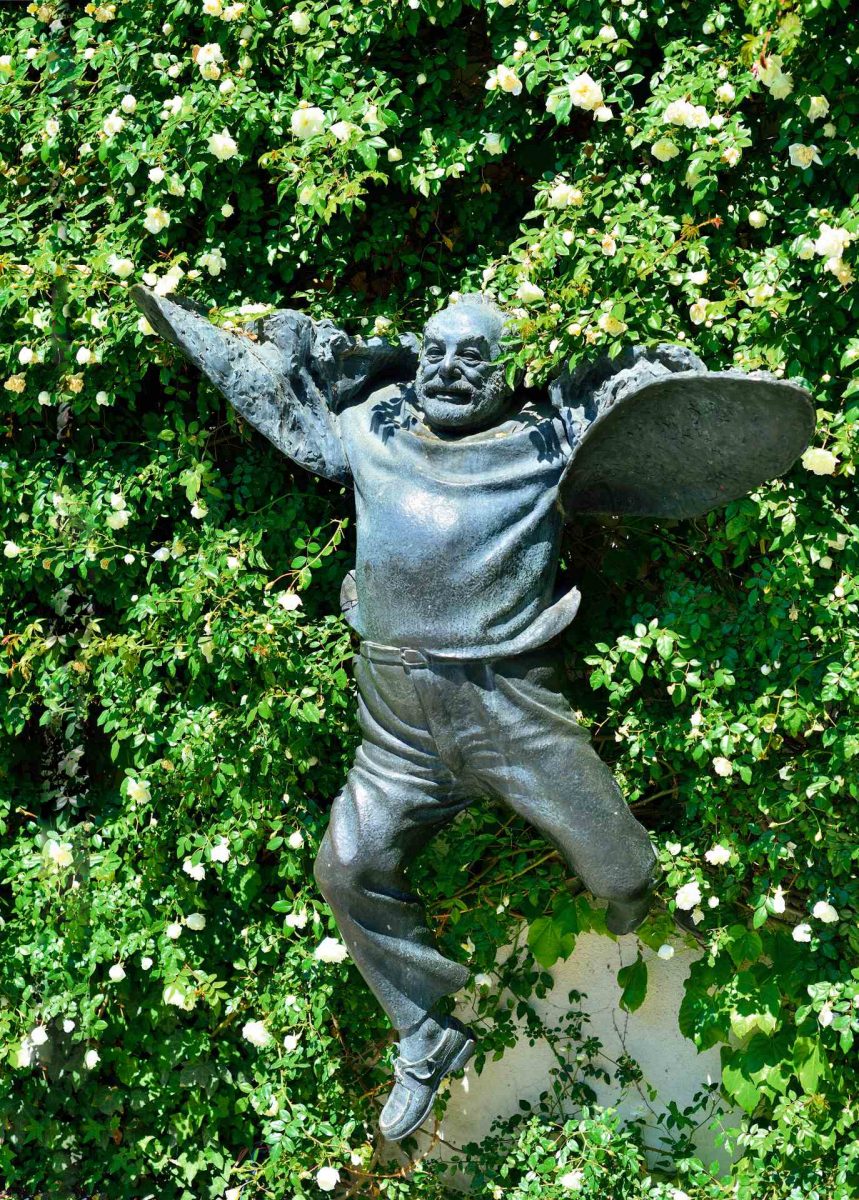

There is a Parajanov Museum in Yerevan. It was founded during the director’s lifetime, in 1988, after an exhibition of his works at the State Museum of Armenian Folk Art. Today, it is an iconic destination for fans of this film making master. It stores over 1500 items, from the interior of Parajanov’s Tiflis house and his legendary collages to women’s hats and “thalers”: medals with portraits of Alexander Pushkin, Peter the Great, and Nikolai Gogol that the director made in prison out of kefir bottles’ aluminium caps. A replica of these medals, known as Parajanov’s Thaler, is a commemorative trophy for the most honored guests at the Golden Apricot International Film Festival in Yerevan. The most inspiring monument to the great film director is located in Tbilisi. It recreates the famous photograph by Yuri Mechitov, who captured Parajanov in the middle of a jump: weightless, daring, as if casting off the burden of earthly woes.

Photo: parajanovartlab.com, russiancollage.ru, shutterstock.com