Text | Sophia Bagdasarova

Great food

Bulls – to be more precise, wild bison, aka bison, appear in the works of artists as soon as this occupation itself appears, that is, in prehistoric times. It is bison and their relatives, the now extinct aurochs, together with other animals important for survival (mammoths, deer and horses) that are the main subject in the majority of prehistoric caves decorated with paintings of cavemen. The bulls of Altamira are the most famous (because it is the first cave found), but their silhouettes are also found in many other underground complexes – Chauvet, Lascaux, Nio, Combarel… In fact, they became a symbol of the whole epoch. The figures of the animals are usually depicted in profile and masterfully painted with natural dyes – ochre, sanguine and charcoal. The modern viewer is fascinated by how the cavemen managed to fill these drawings with energy and create a sense of running. Of course, this interest of prehistoric people to bison was due to the fact that it is them they actively hunted. It is still debatable what exactly they were drawn for, but most scientists agree that it was for a magical, ritual purpose – to ensure good luck in the hunt.

Music of the sun

For a long time, lyres from the Sumerian city of Ur in ancient Mesopotamia were thought to be the oldest stringed musical instruments in the world. But now they have ceded the palm to instruments found during excavations in Russia, in the Maikop archaeological culture. However, the Urals lyres are still the most famous – because of their beauty. During the excavations of 1922-1934, four lyres were found – one silver, the rest gold, and all decorated with bulls’ heads. One head, however, is without a curly beard – and so it is assumed that it is not a bull but a cow after all (just don’t tell me that bulls don’t have beards either, in Sumer, apparently, that was not the case!). The most photogenic of these liras is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The bull’s beard here is made of lapis lazuli the color of heaven. Ancient texts tell us that this particular bull with an azure beard was the Mesopotamian sun god, Shamash, who, like the sun, was regularly sent out into the dark side – the netherworld – and was extremely powerful. Apparently, that is why the lyre’s body is decorated with reliefs on the theme of funerals and funeral cults.

God’s Animals

We all remember that the ancient hero Theseus went to the island of Crete and killed the Minotaur monster, a man with a bull’s head, in a labyrinthine palace. However, scientists have proven that the ancient Greek myths are only a very faint echo of the true attitude toward bulls on Crete. Judging from the frescoes and objects found during excavations on the island, they were worshipped as sacred, royal animals. Poseidon was also believed to be an ox that lives underground, and when he gets angry, earthquakes (which the Cretans were very afraid of) occur. The famous fresco with the image of acrobats on the bull’s back, as well as other objects with this subject, of which there are many, gave rise to the theory that in Crete there was a sacred act – a dance with a bull, a ritual leap. Modern athletes say that it is unrealistic to make such a thing happen, but there is no getting away from the evidence in the art.

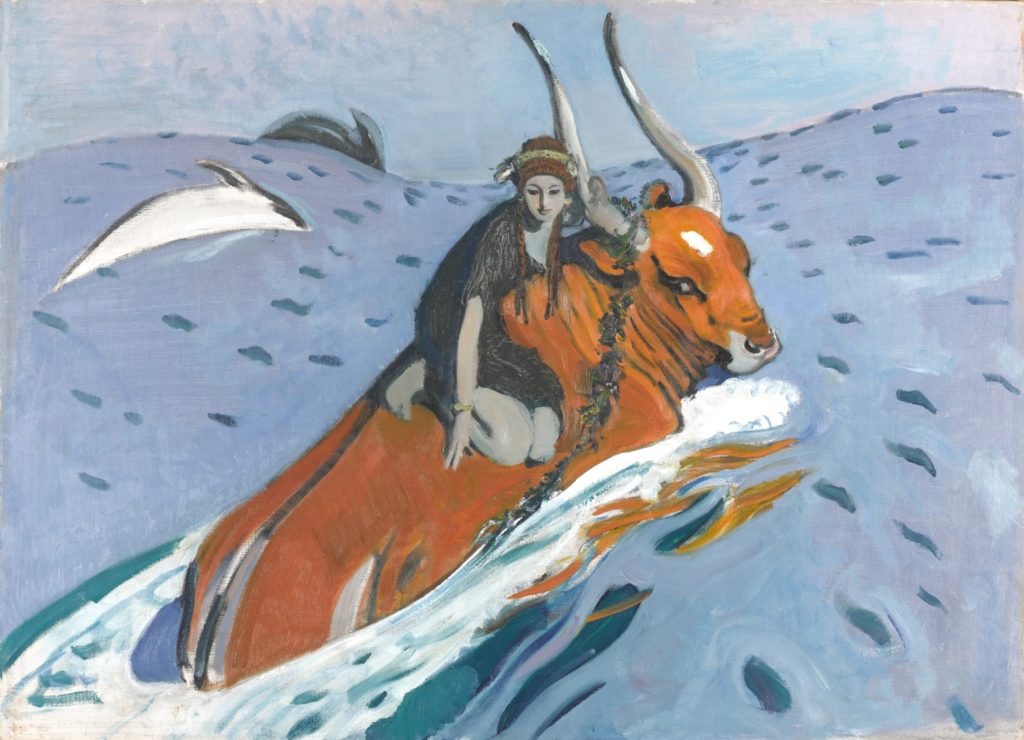

Allegory of Courtship

Bulls and cows appear frequently in New Age paintings, just as they have in everyday life in every century (except the last). But the most popular subject was probably the story spawned by the same Greek mythology, and again on a Cretan theme. It is about the kidnapping of Europa, a princess from Phoenicia (the territory of modern Lebanon). The Greeks said that Zeus, falling in love with her, turned into a bull and swam a good chunk of the Mediterranean Sea with the princess on his back to take her to the still deserted Crete. There she bore Zeus children, who founded a royal dynasty – and that’s why the Cretans worshipped the bull. There are countless paintings on this theme, but one of the indisputable masterpieces is an early twentieth-century canvas by Valentin Serov, which combines the precision and elegance of the Art Nouveau lines with stylization of ancient art: Serov sketched the girl’s face from an archaic bark statue, and he copied the long bull horns from ancient drinking rhytons in the form of a bull’s head.

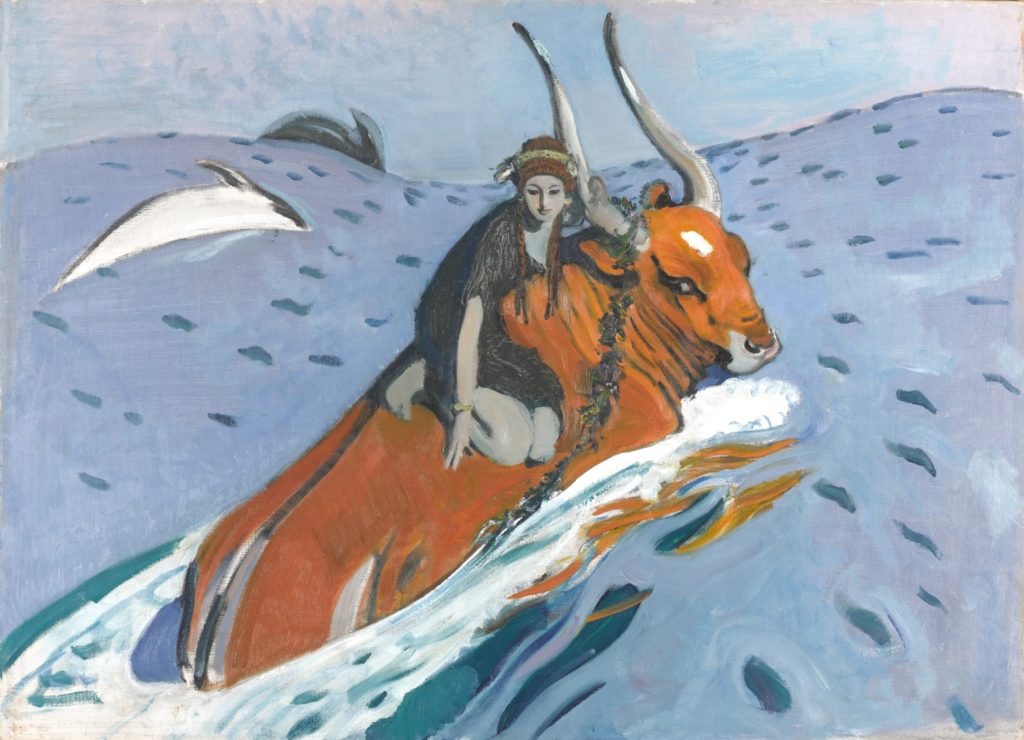

Dance with Death

No one knows where the custom of bullfighting came from in Spain. It is suspected that it happened in times immemorial and has something to do with the same cult of worship that inspired the “bull dance” on Crete. Perhaps in Crete it was a graceful form of human sacrifice using animal horns. So it should not come as a surprise that in Spain the bullfighter also risks his own life. Bullfighting is characterized by fierce ritualization and colorful costumes. No wonder it has attracted the attention of artists for centuries. Of course, it was the locals who left the most paintings, but they (even Goya) often do so in a down-to-earth, life-descriptive way, as if they were itinerants. Of course, the canvases by the Impressionists are magnificent. And a separate reason to be proud – the works of Russian masters, which are both romantic and tragic. Bullfighting was painted by many people – Surikov, Savitsky, Osip Braz, Peter Konchalovsky, Kliment Redko … And recently at Sotheby’s for 677 thousand pounds sold a canvas by emigrant Pavel Chelishchev, who visited Spain in 1934, along with his bohemian friends, including the famous royal photographer Cecil Biton. Chelishchev chose an unexpected angle on the bull…

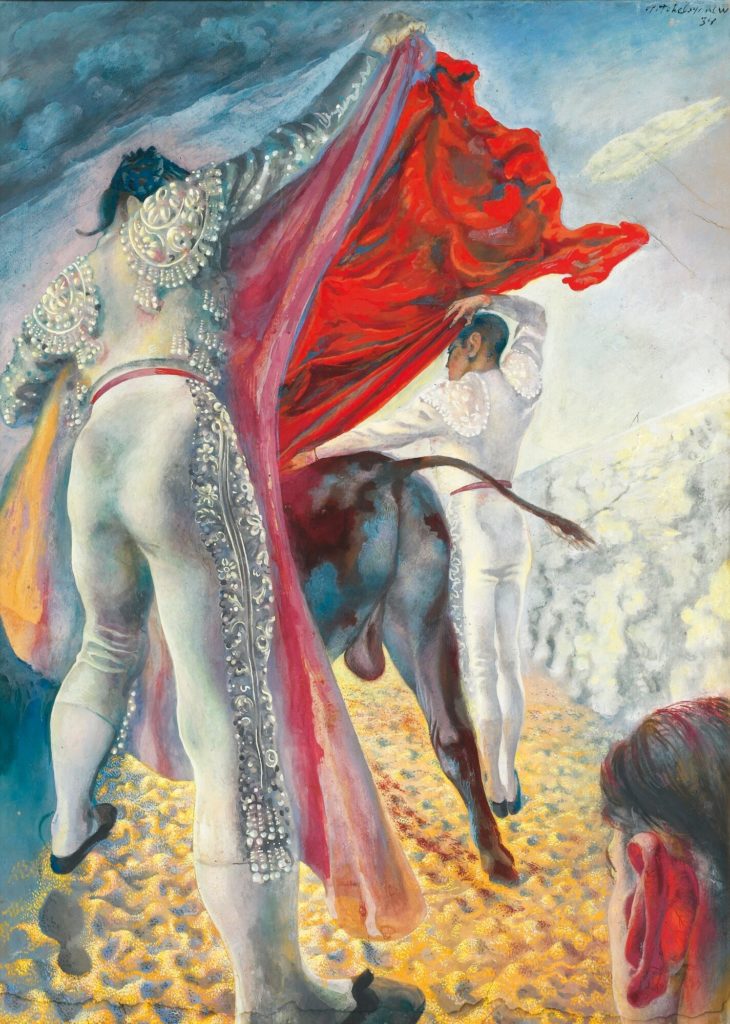

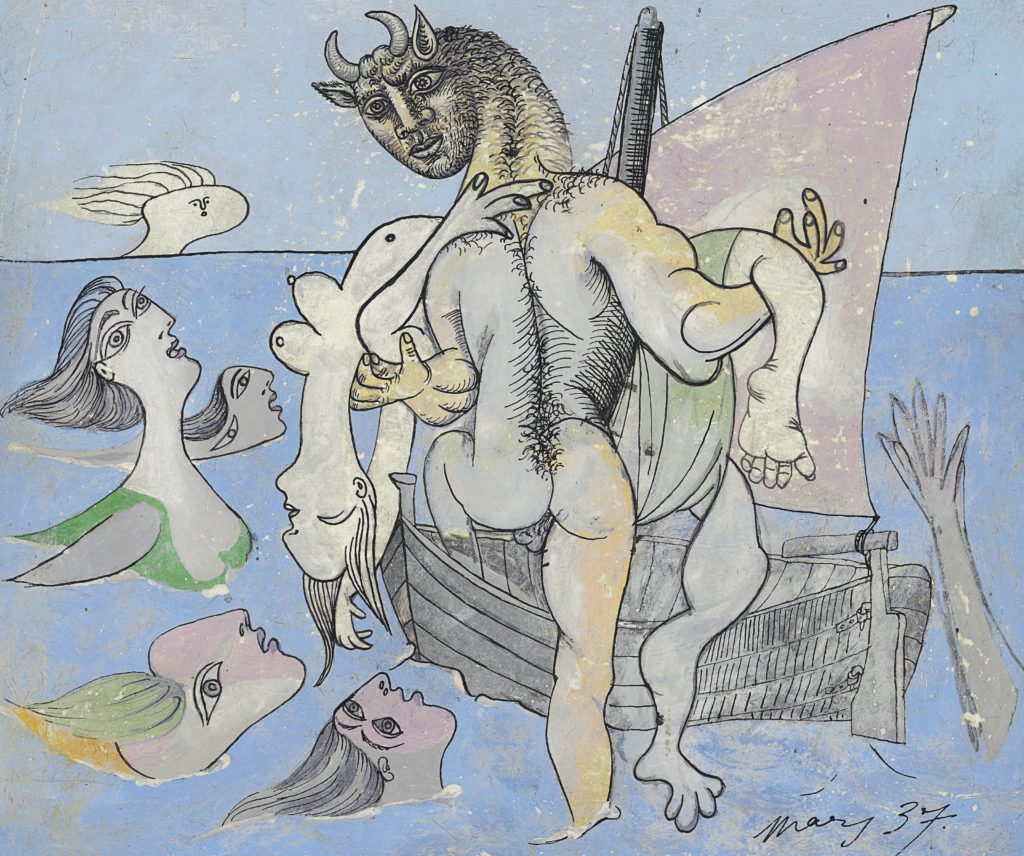

Crazy Visions

For the Spaniard Picasso, who grew up on bullfighting and classical myths, the bull – or rather the Minotaur, the man with the bull’s head – became one of the cross-cutting themes for many years. He associated himself with the fierce Minotaur, torn by passions. He even made himself a giant mask with a bull’s head (several photographs of Picasso wearing this mask have survived). Bulls, both heads and whole, appear in his paintings, prints, drawings, sculptures (including the legendary redimage of 1941 – a head made from the seat and handlebars of a broken bicycle) and even in the glaze painting of plates. The horned head floating in the air is one of the most memorable images of Guernica, dedicated to the bombing of a small Spanish town. From the works in the Minotauromachia series, as if through the pages of a diary, one can study the stages of Picasso’s relationship to the women in his life. These monstrous transformations are fascinating not only because of the artist’s skill, but also because he uses the bull, one of the oldest, archetypal subjects of human art.

A symbol of an era

A rare example of a New Age sculpture that makes it immediately obvious what is being depicted! “The Attacking Bull” by Arturo di Modica was installed in 1989 in Manhattan at the foot of the New York Stock Exchange. The animal furiously flaring its nostrils is an allusion to stock traders, “bulls” (gamblers on the rise), and the statue itself was inspired by Black Monday, the 1987 stock market crash. The sculptor wanted to create a symbol of the power of the American people – but it turned out to be something more significant. Bible-savvy Americans immediately thought of the Golden Calf, an Old Testament symbol of unbridled worship of money and rejection of God’s covenants. The “attacking bull” now regularly appears in comic books and illustrations about the coming of the Antichrist (sometimes even the Harlot of Babylon is placed on it). Be that as it may, tourists adore the sculpture, and its miniature souvenir copies are wildly popular. And the sculptor sues their producers because of copyright infringement…

Photo courtesy of WIKIMEDIA.ORG, TRETYAKOVGALLERY.RU, PENN.MUSEUM, SOTHEBYS.COM, CHRISTIES.COM, shutterstock