The Les Fauves Russes exhibition explores how scandalous French artists transformed Russian art.

The early 20th century was an especially turbulent time for the visual arts. Just as the uproar over Impressionism — which broke the dominance of realism and rekindled artists’ passion for color — began to fade, a new movement emerged on the wave of Post-Impressionism: Fauvism. Fauvism was first brought into the spotlight at the 1905 Autumn Salon, when Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Henri Manguin unveiled their bold, explosive works, shocking the prim and proper audience. The critic Louis Vauxcelles called the rebels “wild beasts” (les fauves) and took pity on the sculptor Albert Marque, whose work happened to be exhibited in the same room — “Donatello among the wild beasts,” he remarked. Thus began a story that reshaped the landscape not only of French art but of Russian art as well. This story is explored in detail in the exhibition Les Fauves Russes, a joint project by the Museum of Russian Impressionism and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Surprisingly, the exhibition opens with a painting you’d never expect to see: a work by Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat — the only one of its kind in Russia. It was brought from the Russian Museum to help viewers understand what audiences at the beginning of the 20th century must have felt when confronted with the Fauves’ works — their wild color combinations, lack of shading, and disregard for traditional perspective. The exhibition’s design also references the events of the 1905 Autumn Salon. The metal bars hint at the “cage for the wild,” as Vauxcelles famously described the room with the Fauves. And the bright yellow walls evoke the exhilaration the artists felt from pure, unblended color.

Fauvism made its way to Russian soil almost immediately after it first emerged. However, Russian artists didn’t stop at borrowing — they brought much of their own to the movement. One reason was limited communication: not everyone could travel to Paris to see the works of the fashionable artists in person. Even the collections of Sergey Shchukin and Ivan Morozov didn’t quite remedy the situation. The former, despite his passion for Matisse, paid relatively little attention to the Fauves, while the latter was reluctant to welcome visitors into his mansion. As a result, Russia’s own “wild beasts” emerged at the crossroads of various styles and movements. They were influenced by Symbolism and Impressionism — and especially by Primitivism, even more so than the French artists.

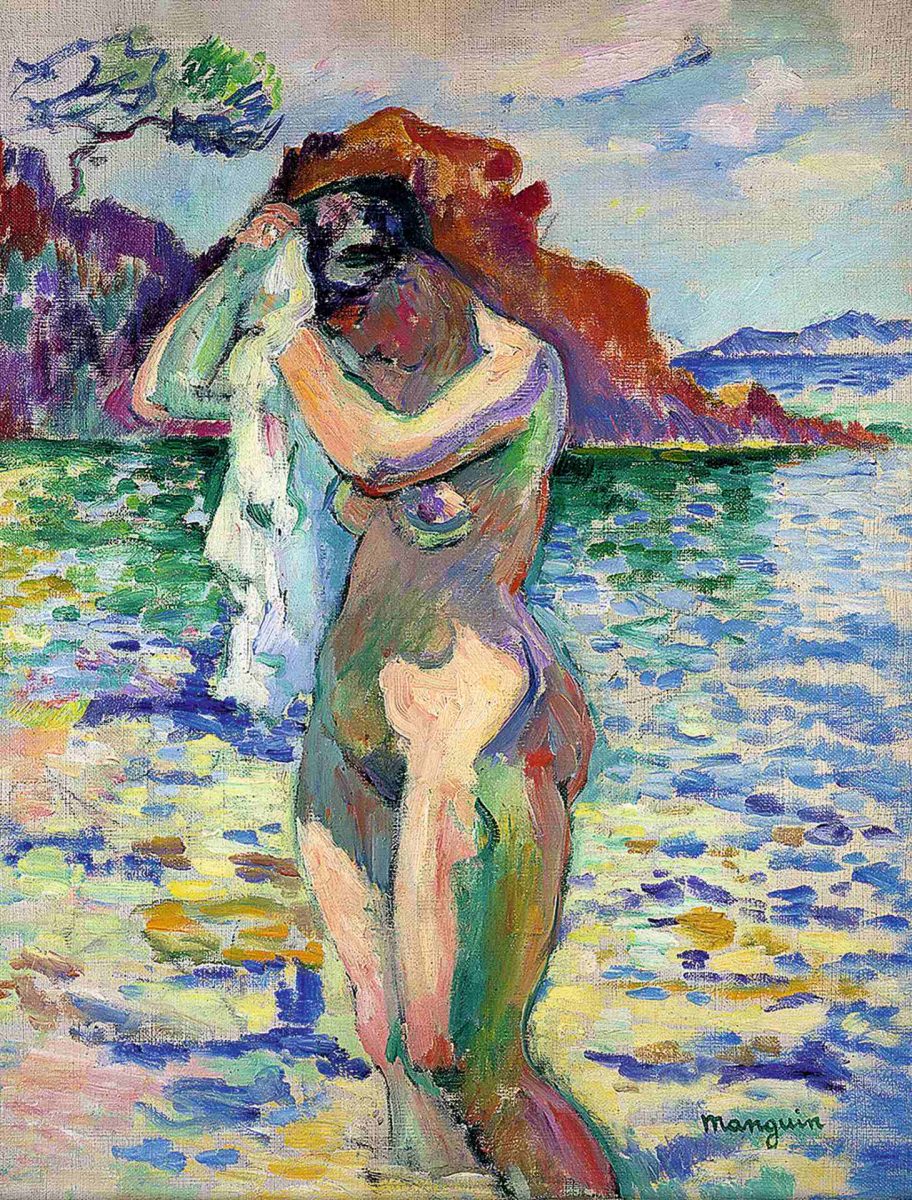

The exhibition at the Museum of Russian Impressionism places Russian painters alongside their foreign counterparts, allowing viewers to appreciate how, for instance, Manguin, who came out of Impressionism, echoes Aristarkh Lentulov — though the Frenchman’s lilac-green combinations shift to green-pink hues in the Russian artist’s work. Incidentally, it was Impressionism that became the starting point for the Russian avant-garde and freed the artist’s hand. Even radical figures like David Burliuk and Kazimir Malevich fell under its influence. In the landscapes by Burliuk on display, one can clearly see a lyrical Impressionist thread, even though he referred to his early works as “desperate realism.”

Lentulov — like many others — was influenced by Paul Cézanne, the Post-Impressionist painter. Among Cézanne’s admirers were other “wild ones” as well — including Pyotr Konchalovsky, Ilya Mashkov, and Robert Falk. That said, not all Russian artists — even the most prominent ones — embraced the widespread fascination with Cézanne. Valentin Serov, for example, mocked his student Vasily Rozhdestvensky, calling his academic nude study “a green parrot.” Mashkov also drew criticism from his teacher Serov, especially after returning from Europe and beginning to paint nude bodies in blue, green, and red.

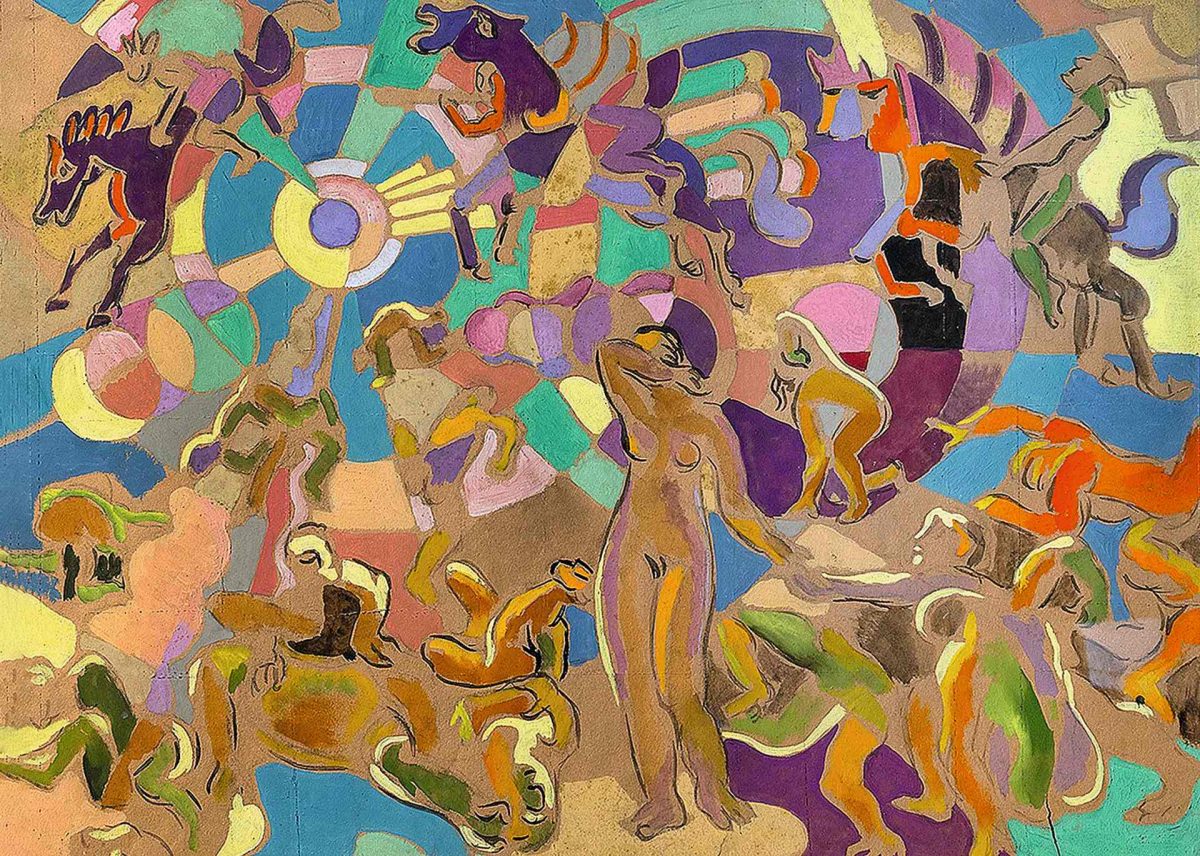

Some of the “wild ones” were influenced by Symbolism — notably Pavel Kuznetsov and Martiros Saryan. As the exhibition shows, the latter didn’t immediately embrace bold color or begin creating his signature vibrant works. A large section of the exhibition features works by artists inspired by “primitives” — folk culture and the creations of self-taught artists. This section is, of course, highlighted by Mikhail Larionov, one of the leading figures of the Russian avant-garde. The exhibition also includes works by his wife, Natalia Goncharova. In addition to the star duo, it’s worth paying attention to some of the lesser-known names. For example, Illarion Skuye — a painter with a tragic fate who went missing at the front during World War I; only a handful of his easel paintings have survived. Or Iosif Shkolnik, once dubbed the “Matisse of St. Petersburg” — a nearly forgotten artist who lived far too short a life, just 43 years.

Some artists drew directly from Fauvism, having lived and worked in Paris. The section titled “Les Russes de Paris” (after the novel by avant-garde writer and critic Iliazd — Ilia Zdanevich) features nothing but prominent names: Marc Chagall, Nathan Altman, Boris Grigoriev, and Nikolai Tarkhov. There are also some unexpected names — for instance, Christian Krohg, a Norwegian painter known for two famous portraits of Sergei Shchukin, who spent several years living in Russia. Overall, the exhibition makes it clear that without Fauvism, the phenomenon of the Russian avant-garde would not have taken shape. And the special project on the third floor — dedicated to contemporary Russian artists’ reinterpretations of Matisse — reinforces the idea that today’s art, too, would be entirely different without its “wild” component.

Photo: Press Office, Vostock Photo