Prominent art dealers, from Ambroise Vollard to Larry Gagosian, run the art world like puppeteers. Women are rarely allowed into this “mafia,” but those who have broken through are especially outstanding. One of these women is Nadezhda Dobychina.

When it comes to a list of the first female gallerists, those who traded in Impressionist and avant-garde works while the artists themselves were still alive, the list is very short. The first number in it goes to Parisian Berthe Weill (1865–1951), who had to compete with Vollard himself (sometimes successfully — for example, among her buyers was even Sergei Shchukin). Weill is considered to be the one who first sold paintings by Picasso and Matisse in Paris, and it is also known that the only lifetime solo exhibition of Modigliani was also organized by her. Number two on the list is the famous philanthropist and collector Peggy Guggenheim (1898–1979); she was also an art dealer. But for a woman with such a family wealth, it was more of a pastime: the Guggenheim Jeune Gallery in London traded for only two years, 1938–1939. However, the exhibition project entitled “Dobychina’s Choice,” which the Moscow Museum of Russian Impressionism opened this year (until September 24), makes Peggy Guggenheim give way — for someone else, also a very enthusiastic lady. So, who is she?

Until recently, the biography of Nadezhda Evseevna Dobychina (1884–1950) was known to a few erudites. But now, the exhibition’s curators hope it will take a more prominent place in art history courses, art business, and of course — in the history of feminism.

Nadezhda Dobychina, a native of the Fishman Jewish family from Orel, married a local nobleman and moved to St. Petersburg, where she enrolled in courses at the biological laboratory. This led her to work for several years as a secretary for exhibitions organized by Nikolai Kulbin, an artist as well as a medical laboratory teacher. Figuring that she could be as good as Kulbin, in the fall of 1911, the young woman founded her own, as we would say today, the gallery. It was called the “Art Bureau of N. E. Dobychina” and served as an intermediary between artists and the public for the sale of paintings and fulfillment of art commissions. Nadezhda was right in her predictions — her energy, temperament, ability to establish contacts, and bring things to an end brought her Bureau great success.

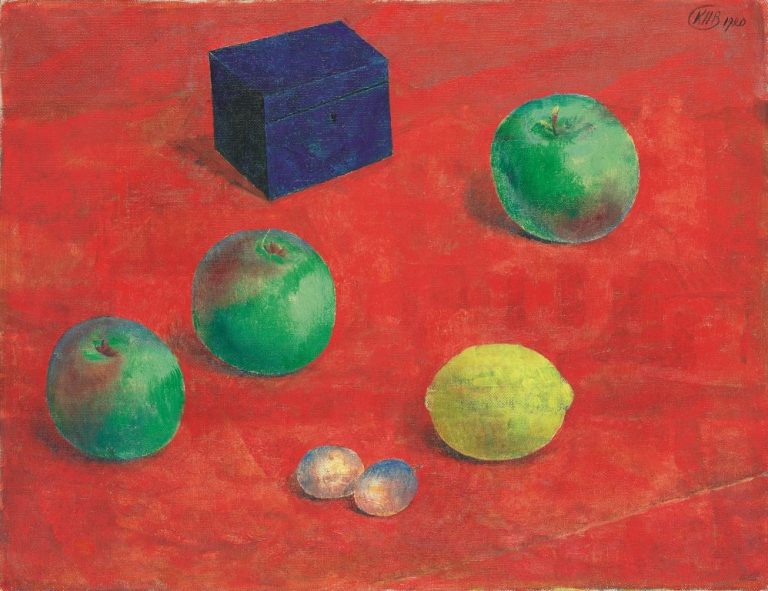

The list of novice artists who were supported by Dobychina both on the eve of World War I and during the war years, today makes art dealers cry with envy and admiration. It was she who arranged the first solo exhibition of Natalia Goncharova in the capital. She was also the one who showed the artworks of Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky in detail for the first time in St. Petersburg. It was in the halls of her Bureau that the legendary Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 was held, where the public saw Malevich’s Black Square for the first time. Nadezhda Evseevna tried to gradually embrace the whole spectrum of artistic currents that were flourishing in pre-revolutionary Russia. And not only those in Russia: she failed to bring Picasso to St. Petersburg only because World War I interfered. She was nicknamed “Durand-Ruel in a skirt,” comparing her to the famous French marchand. The exact size of her earnings as a gallerist is not known, but during this time, she managed to assemble a very impressive collection of works by those who are now considered the “leading names.”

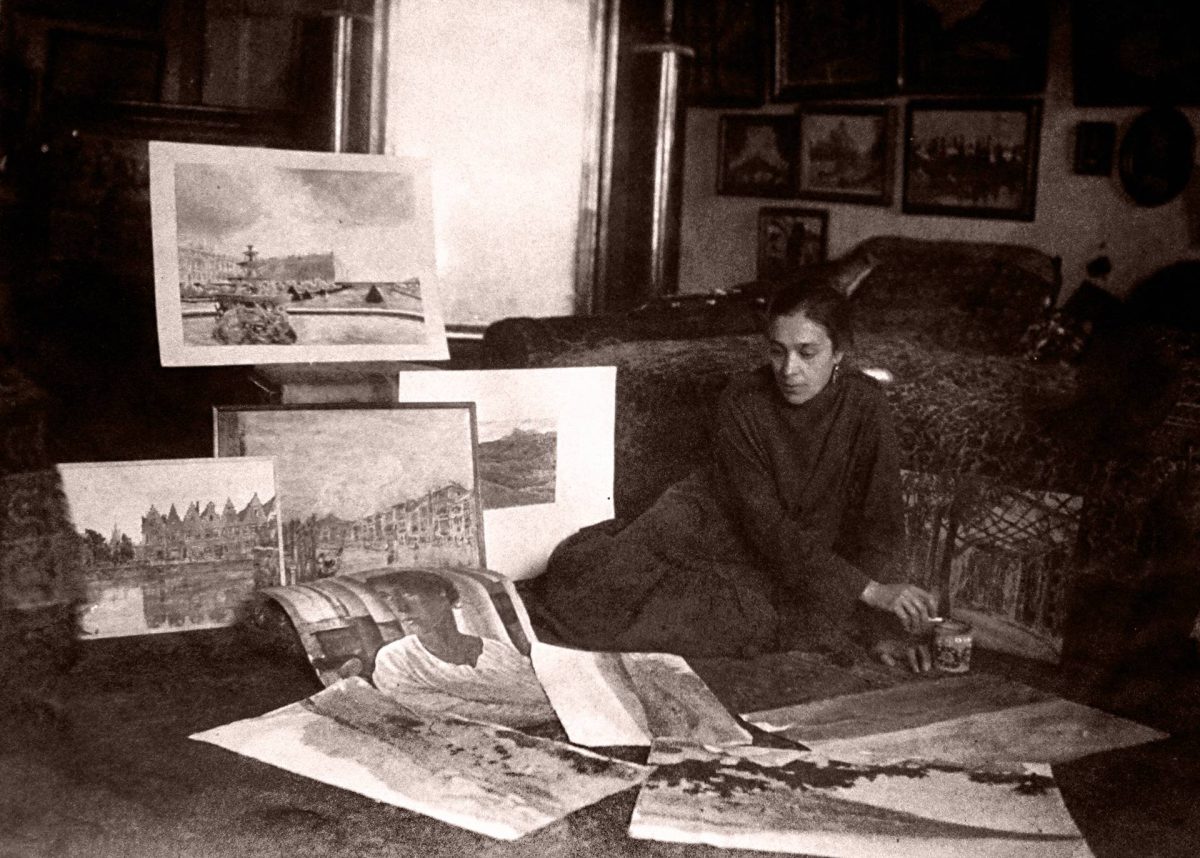

After the revolution, Nadezhda Evseevna had to stop commercial activities. She did not manage to turn her Bureau into a state structure, which would have been engaged in exhibition activities, largely because of her rebellious temperament and freedom-loving nature. In the following years, she headed the Art and Industry School, worked at the Russian Museum and the Museum of the Revolution. Nadezhda succeeded in keeping her collection from being requisitioned, but gradually the paintings had to be sold off — a process that was continued by her heirs. Therefore, for the current exhibition in Moscow, the best state museums of the country have provided the most important works from their collections, perhaps for the first time drawing attention to the fact that they are all connected with the activities of this bright and enthusiastic woman. Well, you can look into her face thanks to portraits painted by Alexander Golovin and Nicholas Benois, and drawings by Konstantin Somov and Robert Falck.

Photo: press-office