Signature emblem, functional detail, decorative flourish, form of self-expression, or simply a beautiful trinket — what exactly are car mascots?

The romantic origin story of hood ornaments traces back to the figureheads of sailing ships, believed to protect the vessel, attract good fortune, serve as a personal emblem, or even intimidate enemies.

More pragmatic automotive historians, however, point to their initially utilitarian purpose. On early automobiles, it was common to refill the radiator with water frequently. The radiator had its own separate cap, located just above the grille and outside the hood. During drives, the cap could become extremely hot — so a sculpted, protruding “handle” made it easier and safer to unscrew. In some cases, the ornament itself doubled as a temperature gauge, often with a touch of artistry. One memorable example is the mascot from Oleo Magneto, a spark plug manufacturer: shaped like a human head, it would emit steam from its nostrils when the engine overheated.

Naturally, car designers couldn’t ignore such a perfect chance to give vehicles a touch of personality. These were far more than just company logos. Using artistic techniques, automakers created memorable icons — from geometric abstractions and whimsical animals to references to gods and mythological heroes.

One of the first signature hood ornaments appeared on a Rolls-Royce. In 1911, sculptor Charles Robinson Sykes created a figurine called Silver Ghost for Baron Montagu. The factory loved it so much, Rolls-Royce asked for permission to place it on all their vehicles. The female figure, with flowing garments that gave her an angelic appearance — nicknamed The Silver Lady, The Flying Lady, Emily, and most famously, The Spirit of Ecstasy — became a symbol of refined luxury.

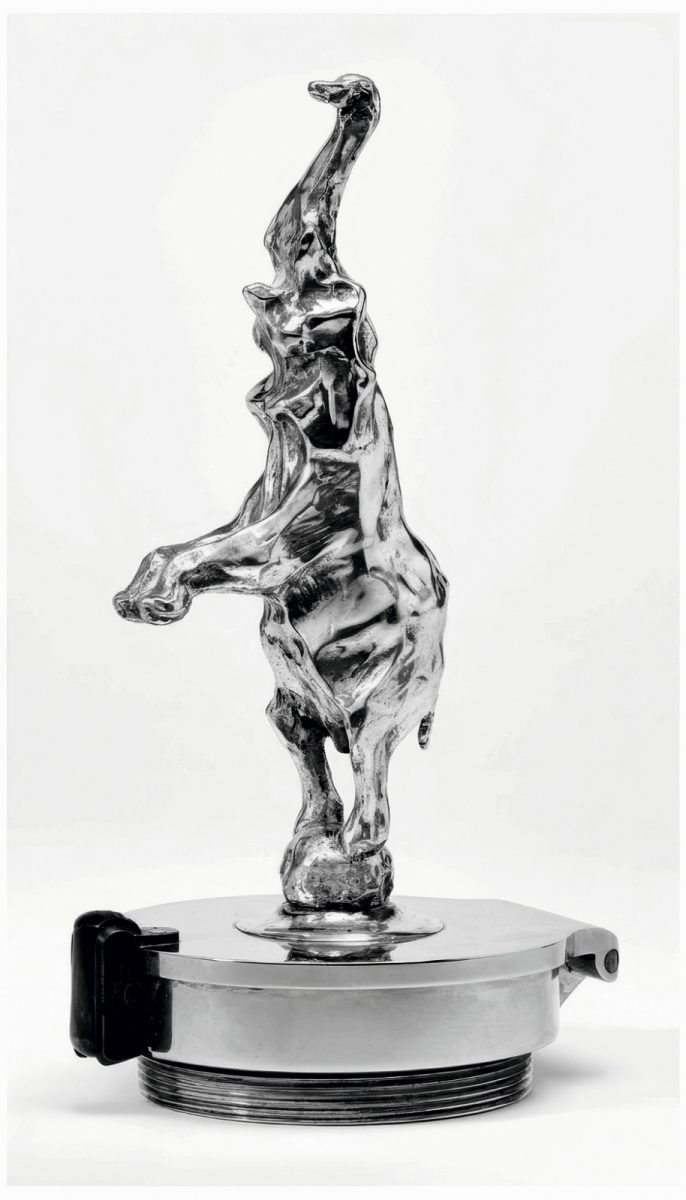

Among the animal-themed mascots, true icons emerged: Bugatti’s Dancing Elephant, Jaguar’s Leaping Jaguar, and Hispano-Suiza’s stork — which became a tribute to French WWI ace Georges Guynemer after his death, as the company had supplied engines for planes bearing the soaring stork on their fuselages.

Eventually, mascot design evolved into an art form of its own. They were cast in metals like brass, zinc, or bronze, often chrome- or silver-plated. Some were made of plastic or even glass. Starting in 1925, famed glassmaker René Lalique designed about 30 hood ornaments, the most famous being Cinq Chevaux (“Five Horses”) for Citroën. He even created a lighting system with colored filters to make the glass mascot glow as the car moved.

Among Soviet-era designs, the most iconic was the leaping deer on the GAZ-21 Volga, though enthusiasts also recall the bison on the MAZ-200 and the bear on the YAAZ-200 truck.

Mascots peaked in popularity during the 1920s and 1930s and continued to appear on hoods through the late 1950s. But as cars got faster, safety concerns grew: in collisions with pedestrians, rigid hood ornaments could cause serious injuries. There was no official ban, but manufacturers gradually phased them out in favor of flat emblems.

Some luxury brands, however, retained their signature look with retractable or folding versions: today, Rolls-Royce’s silver lady disappears into a hidden compartment beneath the hood, while the Mercedes-Benz three-pointed star folds backward. Still, custom mascots remain popular, and auto shows feature an endless array of imaginative interpretations. Unsurprisingly, mascots have also become prized collectibles — ranging from rare, high-end creations sold at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars to mischievously stolen trophies taken under the cover of night — preserving the spirit of a bygone era when high aesthetics and functionality still went hand in hand.

Photo: Vostock Photo