Santorini… A tiny, sun-drenched Greek archipelago in the Aegean Sea, just a 50-minute flight from Athens or a couple of hours’ journey by passenger catamaran from Crete. Although six small islands make up the archipelago, with only two inhabited islands, Thira and Thirasia. You can’t help but wonder at the bustling streets and quieter, more remote parts of Santorini, where the world’s oldest life-form is literally still breathing underfoot as the last active volcano in Greece lies dormant.

Santorini is ready to offer you all the hallmarks of an island holiday in Hellas – warm sea, sandy beaches, fishing springs, historical antiquities and the setting sun sinking into the endless sea horizon – and yet the pulse of the archipelago beats in its volcanic heart. In pre-COVID-19 times, more cruise ships came here in a season than there were days in a year, and day-trippers often outnumbered locals. There is no doubt that once the pandemic subsides, the flow of adventurers will rebound.

Pompeii in the Aegean

The seismic activity here in the centre of the South Aegean volcanic arc is due to the proximity of the Eurasian and African tectonic plates. About 30,000 years ago, the sea island of Strongyli (“round” in Greek), twice the size of the modern archipelago, emerged here from the foam. 5 000 years later, after another earthquake, the core of the island sank into the sea, leaving a crescent-shaped land mass with a bay in the west and a large caldera – the so-called depression in geology forming a cirque basin, formed by the collapse of the crater walls after a volcanic eruption.

People arrived at this unstable land 4,500 years ago; the first pre-Greek settlements are dated to the Neolithic Era. Akrotiri, the most important settlement of the Bronze Age, was a major centre of the region’s flourishing Cretan Minoan civilization of farmers and seafarers. In the spring of 1613 BC, a newly awakened volcano buried its history, and the city’s fate foreshadowed the demise of Pompeii.

Seismologists relish the details of the catastrophic eruption, which lasted several days. At the time, Akrotiri had 30,000 inhabitants – almost twice the population of Santorini today. Excavations have confirmed that people left the island in the aftermath of the eruption, but it is unlikely that any of them survived. About 60 cubic km (!) of ash and volcanic rocks left the archipelago completely covered, a quarter of the largest island sank and the rest fell to pieces – the future Santorini, Thirasia and Aspronisi. A deadly tsunami struck the nearby Cyclades Islands and the northern coast of Crete, while gases rising into the stratosphere turned day into night and lowered the temperature of the planet for two whole years.

Scientists find evidence of that catastrophe in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere. According to the hypothesis, the echoes of the Minoan eruption, which destroyed the ancient civilization, came down to us in the myth of sunken Atlantis. Its traces are also seen in the natural cataclysms described in the Bible as the “Egyptian plagues”.

The possible existence of an ancient settlement here was first spoken of in the 1860s, during the construction of the Suez Canal. At that time Santorini became a centre of extraction of pumice, which was used for the production of seawater-resistant cement used in construction. The extraction was accompanied by numerous finds of artefacts of archaic culture, which could not fail to interest antiquities enthusiasts. However, systematic excavations started only in 1967 and were a success.

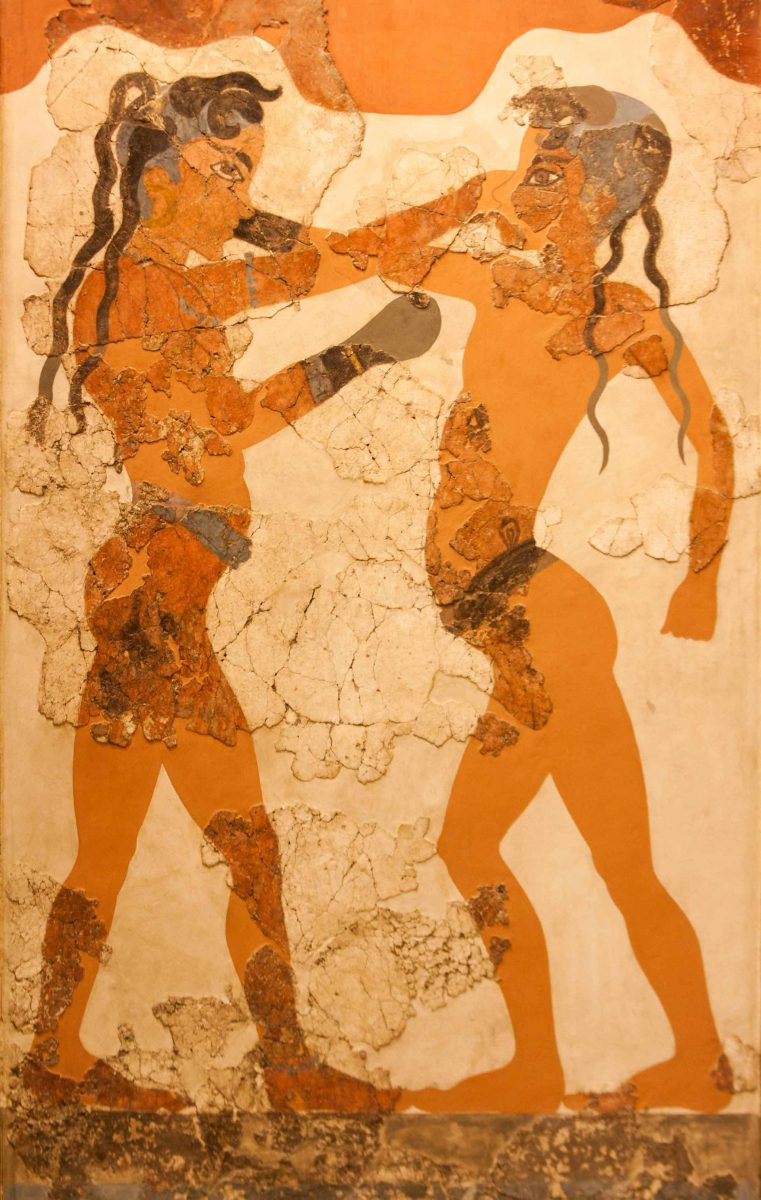

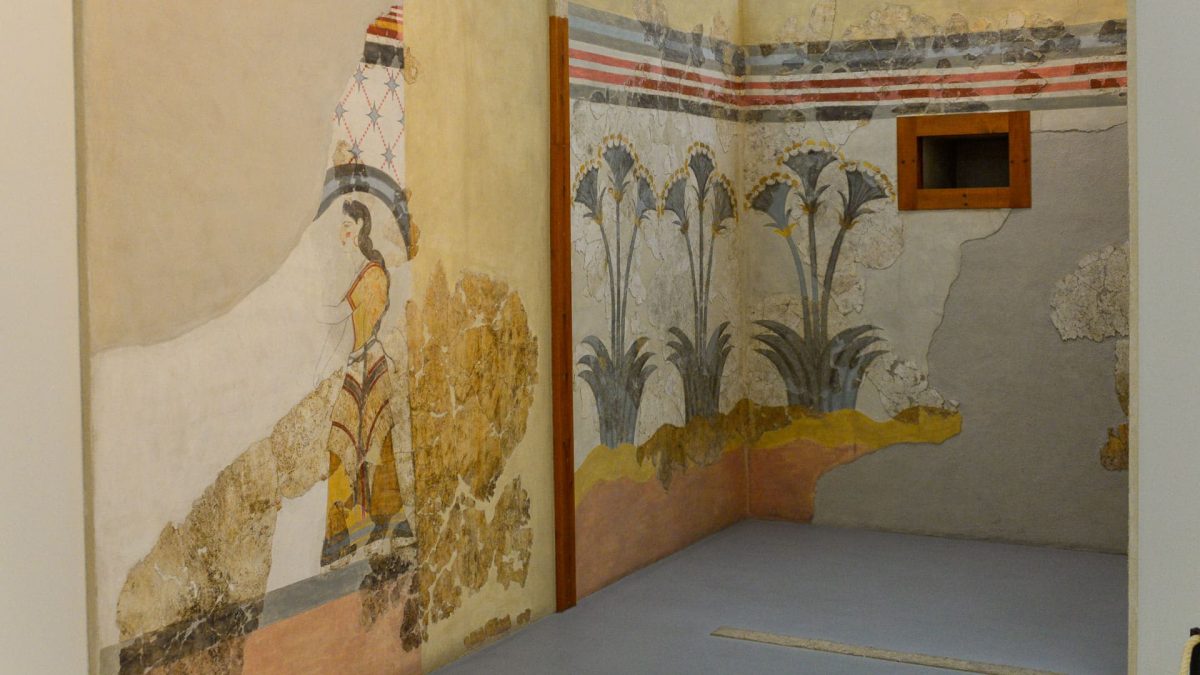

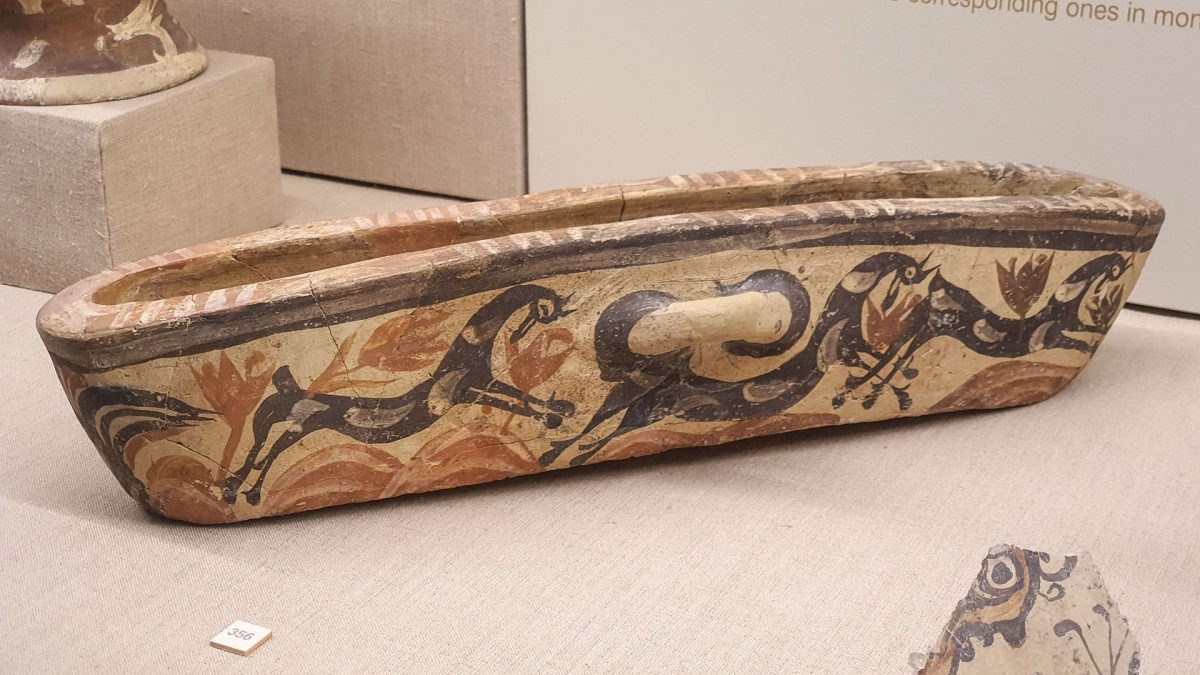

Archaeologists discovered a town of about 20 hectares buried under volcanic rock, with two to three storey buildings and an elaborate drainage system. Thousands of fragments of ceramics, furniture, utensils, tools and examples of ancient Cretan writing were recovered. However, the most valuable are the wall paintings used by the inhabitants of Akrotiri to decorate their homes.

Boxer-boys and fisherman with bundles of mackerel, female figures dressed in festive Aegean fashion, ship’s fleet, spring landscape with blooming lilies and flying swallows, monkeys and antelopes (by the way, neither of them are found on the island) – this is just a partial list of the subjects of the frescoes found here. Most of these Minoan masterpieces have long since been moved to the Archaeological Museum of Athens, but an organised visit to the active excavations remains an attraction that is open to tourists.

In 2015, the Russian IT company Kaspersky Lab sponsored the archaeological research on Santorini, so our compatriots can feel some involvement in the study of traces of a vanished civilisation.

The island of St Irene

Its advantageous location at the crossroads of the Mediterranean trade routes did not attract only the Minoans to the area. Traces of Phoenicians and Egyptians have been found here, and in the 9th century BC seafarers from Sparta founded their colony here, the Ancient Thira. In the 5th century AD the Byzantines built the Basilica of St. Irene, which gave the island its current name.

During the Middle Ages, the Franks, Venetians, Ottomans and common pirates of all stripes succeeded each other. Throughout all this time their life remained life on a volcano with the inevitable blows of fate in the form of earth tremors. The remains of five ancient fortifications, known locally as castles, survive from the Middle Ages. The most important of them, Skaros, was the fortified capital of Santorini until the 18th century, but after another earthquake the inhabitants abandoned it.

Donkeys versus cable car

Today’s capital of the archipelago, Fira is just a small town on the rocks of the caldera with hotels, restaurants, cafes, cinemas, shops and the old port, Ormos. The shallow harbour cannot accommodate large ships, so they anchor in the waters and the process of unloading passengers resembles a landing operation. Ormos is connected with Fira by 600 stone steps leading steeply upwards. Few tourists are willing to make the journey on their own, especially if they have a choice between authentic and modern modes of transport. The 300-metre cliff face can be climbed either the old-fashioned way, with donkeys and mules, or by cable car. The difference in climbing time is insignificant and the cost in both cases will be around 5 euros.

There is a bus station in Fira, which connects the capital with the other settlements on the island. There are a dozen or so bus stations, all of which are rather mountainous or coastal villages. The most important, apart from Fira, are Oia and Pyrgos. The former is proudly called the most photographed village in Greece. It stands 150m above sea level and is famous for its spectacular sunsets, which attract hundreds of visitors with their cameras. Pyrgos, the highest point of the archipelago, offers equally impressive panoramic views. A striking colour accent that photographers will appreciate are the many domes of the local churches, traditionally painted in the national colours of Greece, white and blue.

The oldest surviving church, the Bishop’s Panagia in the Byzantine style, was built at the end of the 11th century. Most of the local churches are either a single-nave basilica with a dome or a small cross-dome church. Sometimes the dome is crowned by a Renaissance lantern. Until the most recent devastating earthquake in 1956, there were an estimated 260 churches and chapels on the island, and although the elements took heavy damage, a good proportion has been restored.

The most important museums in Santorini are the Prehistoric Thira Museum, dedicated to the earliest period of the island’s inhabitants, including the heyday of Akrotiri; the Archaeological Museum, with a large collection of Hellenistic sculptures and frescoes; the Museum of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Relics; the Naval Museum; and the House Museum of George Argyros, a 19th century wine merchant.

The volcanic soil is said to give the local grapes their distinctive flavour and, although Greece is not a major wine producer, locally produced beverages are a must-taste. Santorini is home to the country’s largest wine company, Butari, and its wineries are open to tourists. The two main local wine specialities are Vinsanto (red) and Nykteri (white).

Life on a volcano

A must-visit destination is the two small islands at the centre of the caldera, Palea Kameni and Nea Kameni. The locals refer to them simply as ‘the volcano’.

Nea Kameni is the ‘youngest’ land in the Mediterranean. Here are just three milestones of its interesting chronology: the “young man” began to form about 450 years ago, over the past 150 years. It has tripled in size, and the age of the upper layers of its frozen lava is insignificant in terms of geology – just over 70 years!

One of the Jesuit Fathers, who witnessed with his own eyes the birth of a new land in the early 18th century, wrote the following account of the event: “The fishermen discovered the island early in the morning (May 23, 1707), but could not make it out, believing it to be a shipwreck, which was adrift at sea. As soon as the fishermen realised it was a new island, they were frightened and rushed ashore…”

Nea Kameni is still virtually devoid of vegetation and is famous for its unforgettable primeval landscape. Palea Kameni is 1,500 years older than its volcanic counterpart and is famous for its bathing hot springs.

In 1995, the European Union set up an entire institute to study and monitor Santorini’s volcanoes. This volcano observatory has entwined the archipelago with a network of chemical, seismic, thermal and ground deformation monitoring stations. Its main task is to ensure the safety of the inhabitants and their many visitors. After all, scientists have no doubt: the main question is not whether the volcano will wake up again, but when it will do so.

Photo: shutterstock.com, santorini-more.com, istockphoto.com, depositphotos.com