There are legends of Vikings and crocheted patterns on jumpers, sheep grazing on the Atlantic coast, mussels freshly caught from the ocean, Iron Age fortresses and deserted beaches… So, there are plenty of reasons to visit the islands in the Atlantic Ocean!

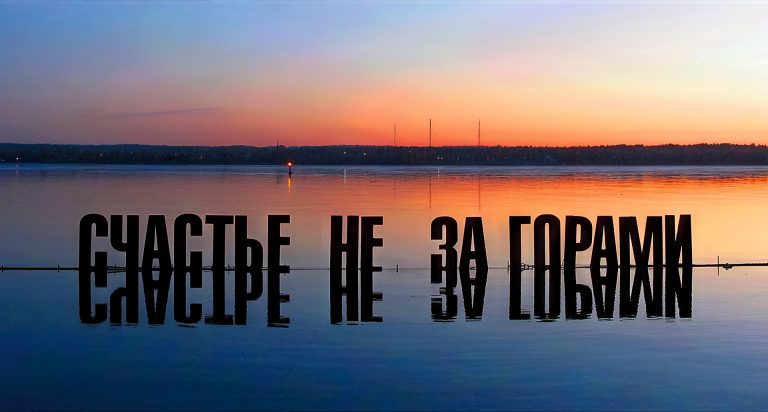

In Shetland, everywhere you look, it’s the most northerly. There is Britain’s northernmost island. There is the kingdom’s northernmost lighthouse. There is the northernmost city. There is the northernmost castle. There is the northernmost brewery. By British standards, an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean is the true far north. Although geographically the Shetland Islands are located on the same 60th latitude as St. Petersburg.

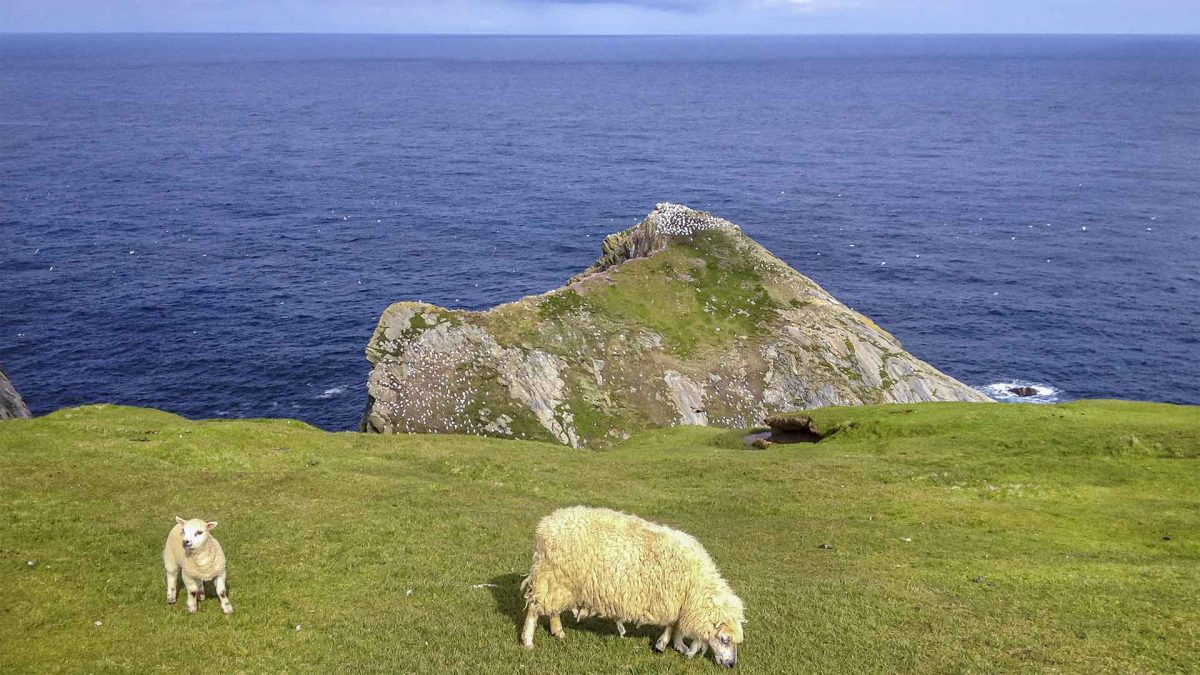

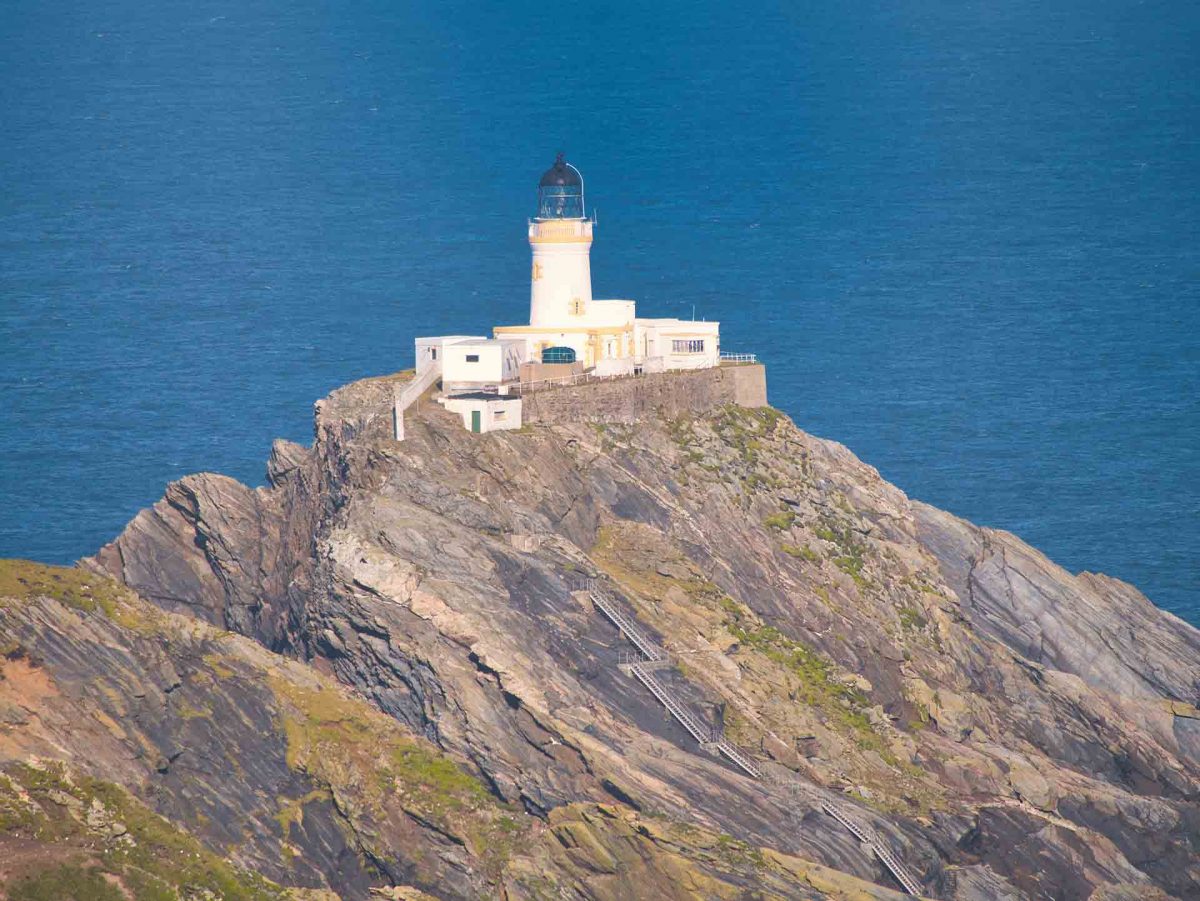

The climate, by the way, is similar. It’s not very warm here, even in summer, and it’s not dry at all. Long deserted sandy beaches in sunny days look almost like Mediterranean ones, but you will hardly swim in the icy water of the Northern Atlantic. On the high cliff of the Hermanesse Peninsula, it is time and place to remember the local legend of how two giants once lived here and fell in love with a mermaid. She promised to marry whoever would get to the North Pole with her. However, the giants couldn’t swim and drowned, becoming islets: one of them is Muckle Flugga, where there’s a romantic white lighthouse (it’s Britain’s northernmost lighthouse), and the other is Out Stack Rock, the northernmost point of the British Isles.

Yes, if you look north from Hermaness, there’s only the sea ahead as far as the pole, no more land.

Between Vikings and Scots

A turboprop plane with a Scottish tartan on its tail comes in for a landing at Samborough Airport. The porthole, like the zoom of a lens, brings the blue of the ocean and the green of the islands closer. The airport connects Shetland with Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Inverness, as well as the neighbouring Orkney Islands. The rest of the world is only via connections.

Though no, you can still get there by sea. The Shetlands were one of the most popular cruise routes in the North Atlantic before the pandemic (and probably will be again, especially as travel to the islands is now officially permitted).

In the yacht marinas of Scalloway and Lerwick, Norwegian is hardly more popular than English. The Scandinavian coast is only 300 km away, eastwards across the North Sea. The Scottish mainland is 170 km away. The Shetlands, in fact, have lived this way for many hundreds of years, between Scotland and Scandinavia. The islands were conquered by the Vikings in the eighth and ninth centuries. The archipelago officially became Scottish in XV century. Another three hundred years, until the XVIII century, the locals spoke the “Norn”, a variant of the ancient Scandinavian language.

Absolutely all names of capes, harbours and straits of the archipelago, which consists of a hundred islands (only 16 of them are inhabited), are of Norwegian origin. They sound like the saga: Trondra, Vaila, Skerries, Sandvik and Norvik, East and West Burra… Say, Lerwick is the capital of the archipelago and the northernmost English city. Translated from the ancient Scandinavian, it means “muddy, muddy cove”. Now the bay, like the town, looks clean, cozy and welcoming. The main street of Shetland’s capital is packed with shops of local craftsmen and designers, mostly jewelers and knitters.

The new Shetland Museum in Lerwick was opened together by Britain’s Prince Charles and Queen Sonia of Norway. In the town of Scalloway on the oceanfront stands a monument reminding us of an almost unknown page of World War II. Port Scalloway was the base of the Shetland Bus, the “Shetland Bus”, a sea crossing between the Shetlands and Nazi-occupied Norway. Fishing boats ferried refugees from Norway and carried Resistance fighters and weapons back. Local fishermen volunteered for this very dangerous mission. The boats were made at night and in rough seas so as not to be spotted. In all, around 100 voyages were made.

To this day, more than half of the genes in the DNA of the indigenous Shetlanders are from the Vikings. Every souvenir shop carries T-shirts with Nordic navigators in horned helmets. It’s not that the Scandinavian past is not denied in the Shetlands, they are proud of it. Even the UK’s northernmost brewery is eloquently called Valhalla.

Atlantic wool and seaweed gin

Elsewhere, knitted jumpers, scarves, ponchos and caps with intricate, colourful patterns take pride of place in the gift shops. The story behind each jumper begins in green meadows looking out over the Atlantic Ocean, with Shetland lambs renowned for their extraordinarily soft wool.

Shetland wool is a protected designation of origin (such labels are more usual for wine or cheese, but it’s the wool that’s most precious with the island sheep!). For a more natural and authentic feel, you can buy yarn dyed with natural Shetland herb and flower dyes and a book of traditional patterns. Then, on long winter evenings, you can plait the needles with warmth and take your thoughts back to the Shetlands, where fishing nets and crab-nets are as much an integral part of the landscape as Rhodiola rosea blooming on the rocks and furry, pretty ponies. In order to complete the experience, you should also take home a Shetland gin and seaweed to go with your yarn, and then head back to the islands next September for Shetland Wool Week.

There are even rooms devoted to knitting, the Shetland’s premier craftsman (in modern-day terms, creative industry), in the enormous, modern Shetland Museum in the archipelago’s capital city of Lerwick. More attention is paid only to seafaring, shipbuilding, fishing and whaling. The latter remains in history, but the fishing industry is still thriving. Although the Shetlands now make more money from oil and gas extraction.

Maritime traditions on the menu and in museums

Tourists are bound to pay tribute to the Shetland fishermen’s hard work, even if they do not go to the museum. Scallops, mussels, crabs, lobsters, cod and salmon are high on the menus of all the local restaurants and pubs. The only competition is local lamb.

For a more maritime-themed experience, Unst is the northernmost inhabited island in not just Shetland, but the British Isles. Visit Unst Boat Haven, a museum dedicated to traditional ships, sails, fishing gear and even sailors’ songs. It’s not just made with love and soul, like many provincial displays: its collection is truly rich and professionally designed – and this on an island of 600 people! The population of the entire archipelago, by the way, is 23 thousand.

On the island of Unst is another attraction of the British far north – Muness Castle of the XVI century, the most northern in the kingdom. Not to say it’s well-preserved, its location is primarily of interest.

By the way, a visit to Unst is worth hurrying. It may soon be transformed from an island of endless misty meadows and rolling hills where it’s easier to meet cartoonish red-necked stooges, loons and boobies than people, into a technological hub. The British Space Agency has plans to build a spaceport on Unst to launch satellites. While construction is being stalled by heritage experts. It could destroy several monuments.

Ancient stones overlooking the ocean

On the other hand, the Shetland Islands could soon be added to the UNESCO World Heritage List. They are already among the official contenders with a complex of three prehistoric monuments. The most interesting thing is probably the broch on Musa Island. Brochs are circular Iron Age fortified stone towers, and there are several hundred of them in Scotland. The Broch on Moose Island is the biggest of them all, over 13 metres high. It was built by people who lived here a hundred years BC (most likely, the Picts tribes).

The Jarlshof is an archaeological site used to study the history of the Shetlands from 2500 BC onwards, and to show tourists how people lived in the Bronze Age, in round, labyrinthine stone houses. In the Iron Age they built a broch and a protective wall around the settlement. The Picts decorated Jarlshof with patterns carved into the stones. The Vikings brought their own architecture. The so-called “long house” appeared on the same site. Even later, a Scottish mansion appeared there. In the 19th century, Sir Walter Scott, who described Yarlshof in his novel The Pirate, reached the Shetlands.

A third monument in line for the UNESCO list is Old Scantness, discovered during the construction of Samborough Airport. Located next to the Jarlshof, it too looks like a puff-piece of different eras and cultures.

Despite the wealth of history, the most beautiful thing in the Shetlands is the ocean. Yes, we’ll go to a museum and a gin tasting, sit on the terrace of a seaside restaurant, wrapped up in a bright jumper we’ve just bought. Then it’s back to port for a sailboat trip, an orca safari or an ocean fishing trip with a guaranteed bounty of fish.

Photo: istockphoto, wikipedia.org, sixareen.co.uk, tripadvisor.co.uk, shutterstock, dreamstime, brands-hub.ru